Post by Tamrin on May 16, 2009 23:17:51 GMT 10

THE FATHER OF MODERN SPECULATIVE MASONRY

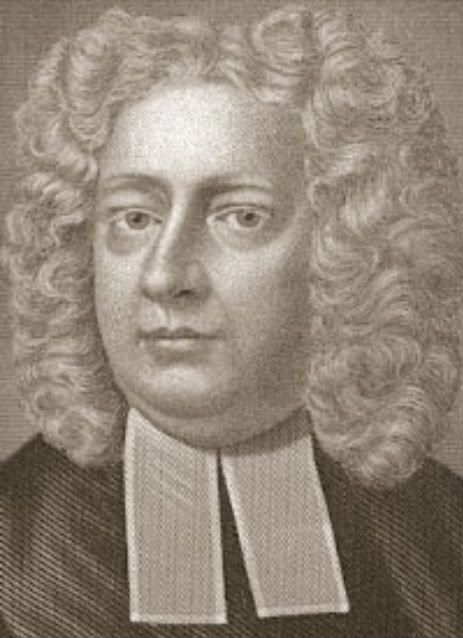

REV. Dr. JOHN THEOPHILUS DESAGULIERS (1683 – 1744)

HUGUENOT, FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY & THIRD GRAND MASTER

Presented to the Hunter Valley College of the Societas Rosicruciana in Scotia

By R.W. Fr. Philip Carter, #8, Nosce te ipsum, 3 June 2006

REV. Dr. JOHN THEOPHILUS DESAGULIERS (1683 – 1744)

HUGUENOT, FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY & THIRD GRAND MASTER

Presented to the Hunter Valley College of the Societas Rosicruciana in Scotia

By R.W. Fr. Philip Carter, #8, Nosce te ipsum, 3 June 2006

Tonight we will briefly examine the creation of Freemasonry, as we know it; especially its principal founder, ‘the father of modern, speculative masonry’, the Rev. Dr. John Theophilus Desaguliers. In doing so, we will be led to conclude that, rather than faithfully reviving the secrets and mysteries of medieval, Operative Stonemasons, Desaguliers and his associates created a novel institution, (with some real or imagined ancient elements, which were, however, more or less distinct, from those of the Operatives[1]). This new institution they contrived to skilfully graft to the four or more London lodges which still perpetuated a few remnants of the rudimentary customs and usages of Journeymen Stonemasons.[2]

The Premier Grand Lodge was established in 1717. In the first year, the inaugural Grand Master, Anthony Sayer, did little other than warm the chair; the following year, the second Grand Master, George Payne, proved to be a competent but otherwise unremarkable administrator; then, in 1719, we find the languishing Grand Lodge revived by the leadership of John Theophilus Desaguliers, after he was elected as the third Grand Master. His extraordinary vision transformed what had been little more than a convivial combination of drinking clubs into a noble and fashionable institution, eminently suited to the dawning Age of Enlightenment. All subsequent Grand Masters have been more or less nominal patrons of aristocratic or royal birth, with their routine duties often being performed by a deputy, (a post to which Desaguliers was thrice appointed).

Desaguliers had been largely credited with the creation of the Premier Grand Lodge.[3] In his Cyclopaedia (p.154), Kenneth Mackenzie tells us:

By his ardour he awoke the energies of the Masons of his time, and after preliminary [and perhaps apocryphal] conferences with the aged Christopher Wren [(1632-1723)], he managed to obtain a meeting of the four London Lodges in 1717, when the Grand Lodge was constituted... Under Dr. Desaguliers the Craft rapidly increased in numerical strength, respectability and influence, many noblemen taking part in the ceremonies, and subsequently officiating as officers. Another point in which Desaguliers took much interest was the collection of anterior documents concerning the Craft; and we are indebted to him for the preservation of the ‘Charges of a Freemason,’ and the preparation of the ‘General Regulations.’In his Constitutions of 1723, James Anderson credited his mentor Desaguliers with having assisted in the work, probably overstating Desaguliers’ role so as to add lustre to what was essentially Anderson’s own creation which, despite having departed far from his initial brief in its production, subsequently gained the approbation of the Grand Lodge. Referring again to Mackenzie’s Cyclopaedia, we find, (pp.154/5):

After retiring from office in 1720, he [Desaguliers] was thrice appointed Deputy Grand Master – in 1723, 1724, and 1725, and he first founded that scheme of charity now known as the Fund of Benevolence. During this period he visited the Operative Lodges of Edinburgh. He afterwards went to Holland, and was W.M. of a Lodge especially convened for initiating the Duke of Lorraine, afterwards Grand Duke of Tuscany and Emperor of Germany, in 1731. He also initiated the Prince of Wales at Kew, at a special Lodge held for that purpose.[4]In Albert Mackey’s Encyclopedia (p.240) we read:

Of those who were engaged in the revival of Freemasonry in the beginning of the eighteenth century, none performed a more important part than he to whom may well be applied the epithet of the Father of Modern Speculative Masonry, and to whom, perhaps more than any other person, is the present Grand Lodge of England indebted for its existence.Mackey also said (Encyclopedia, p.242):

To few masons of the present day … is the name of Desaguliers very familiar. But it is well that they should know that to him, perhaps more than to any other man, are we indebted for the present existence of Freemasonry as a living institution.In an oration, entitled, Desaguliers and the March of Militant Masonry, George E. Main says of Desaguliers:

He took an old dying order and gave to it a philosophy which was peculiarly his own. He added a touch of science, and then a practical concept of the Great Architect and Organizer of the world; into this he breathed a prayer and Speculative Freemasonry was born. Through the force of his own personality he brought to this new institution the important men of England, royalty, the nobility, the elite, the great minds. Because of the purity of its principles, and because of the importance of its early leaders brought in by Desaguliers, Freemasonry since his day has been a living thing, pulsating with the very best that is to be found in man.However, such glowing tributes give us pause when, on the one hand we find Freemasons proudly espousing their ‘time immemorial’ traditions, while on the other hand, Main , in speaking of Desaguliers and Freemasonry, said (ibid.): ‘He wrote most of its ritual.’ And, we read in Mackey’s account (Encyclopedia, p.241): “‘The peculiar principles of the Craft,” says Dr. Oliver, “struck him [Desaguliers] as being eminently calculated to contribute to the benefit of the community at large, if they could be redirected into the channel from which they had been diverted by the retirement of Sir Christopher Wren’.” We may be led to suppose that Desaguliers did indeed redirect them, into, however, an entirely new channel (the influence of Wren[5] is doubtful and was probably invoked in order to legitimise Desaguliers’ innovations).

Looking at The Ritual of Operative Freemasons (Carr), we are struck by the dissimilarities between London’s Guild system of seven degrees and the present three degrees of Craft Freemasonry. The word of each of the first two degrees is entirely different (not simply transposed, as occurred later) to those in use among modern, Speculative Freemasonry and the pillars which feature so prominently in the Speculative degrees have an entirely different significance in the Operative degrees. Moreover, we are told there is no record of the Third Degree among the Speculative Freemasons, or of its Hiramic Legend (Jones, pp.303/322), until around 1726 and, when it did appear, it bore no resemblance to any of the degrees as practiced by London’s Operative Stonemasons.

Well may we wonder what Desaguliers had in mind when creating the Freemasonry with which we are familiar? Our wonderings inevitably lead us to behold the man. Desaguliers was a renowned scientist, becoming close friends with Sir Isaac Newton, (President of the Royal Society[6] from 1703 until his death in 1727), and Desaguliers being, himself elected as a Fellow of that Society. This influence is reflected in Freemasonry’s rituals, with it emphasis on the ‘Hidden mysteries of Nature and Science’, the ‘Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences,’ its call for a ‘daily advancement in Masonic Knowledge’ and, as Hamill and Gilbert tell us:

There seems little doubt that the many Fellows of the Royal Society who became Free masons were influenced by Desaguliers example, and it is surely no accident that no less than 12 Grand Masters were also Fellows of the Royal Society during the 20 years following Desaguliers.Indeed, the idea that Speculative Freemasonry was a product of the Royal Society is among the more plausible theories of Freemasonry’s origins (e.g., Mackey’s History, pp.301/314). However, despite the fashionable prevalence of rosicrucianism in the early eighteenth century, when alchemy was still considered a science, and despite the influence rosicrucianism may have had on both the Royal Society and on Freemasonry, ultimately a direct connection between the two appears to lack a suitable motive: While the practical aspects of Operative Stonemasonry may have aroused some passing interest among the members of the Royal Society, there is little, about Speculative Freemasonry to explain why they would would, as science enthusiasts, wish to involve themselves in its creation. I suggest their common origins can be traced to rosicrucianism, (as a body of thought rather than as a corporate identity).

Returning to Desaguliers, we find another aspect of the man which lends itself to yet another theory which we ought to consider. He was a Huguenot. When Desaguliers was just two years of age, his Reverend father smuggled him to England in a wine cask to escape persecution in France. All Protestant clergy were compelled to leave France while all other Protestants were required to remain, (although many managed to escape). In England, Desaguliers also became a Protestant clergyman, (albeit an Anglican Minister, in keeping with his new home).

A disproportionate number Huguenots were skilled artisans because of which, religious prejudices aside, they were welcomed in most of the countries in which they sought refuge. A disproportionate number were also enthusiastic scientists. Indeed, of France’s Académie Royale des Sciences, we are told (Institute and Museum of the History of Science): ‘The Academy declined after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), when many Huguenot scientists fled France.’ Not surprisingly, London’s Royal Society soon flourished upon subsequently attracting a disproportionate number of Huguenot members, such as Desaguliers (Cryer, pp.156/7). I suggest that it is here, among the Huguenots and like-minded Protestants, that the grain of truth in the theory of Freemasonry’s Royal Society origins may be found.

Indeed, Margaret Kilner, in speaking of the Huguenot chapel in Leicester Square, tells us:

Adjoining the chapel was the house of Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) generally acknowledged to be the world’s greatest scientist of his time... It appears that his close proximity to the chapel enabled him to offer the ground floor of his house for further French refugees from France as a place of worship. Many Huguenots came to worship there.In an address entitled, Huguenot Freemasons, presented to the Huguenot Lodge in London, Rev. Neville Barker Cryer, said (p.154):

… the place of the Huguenot male citizen of the early 18th century in the development and establishing of the English Grand Lodge was notable and extensive.On their continuing influence, Cryer said (p.155):

… no less than one quarter of all the recorded Stewards’ names in Grand Lodge are those of recognisable Huguenot origin – but what of those whose names have, or had soon, become totally anglicised?The Huguenots followed the doctrines of John Calvin. English speaking Calvinists such the Huguenot and Walloon émigrés in England, the Scottish Covenanters, the English Puritans, etc., enthusiastically held to the Geneva Bible, even after the use of the Authorised King James Version had been mandated. In another address, Cryer proves that the V.S.L. in use by the Premier Grand Lodge was indeed, the Geneva Bible. Incidentally, the bond between the Huguenots and the Covenanters was especially strong because of the ‘Auld Alliance’ between the French and Scots, against their common enemy, the English. In the aftermath of the Reformation, and especially in the context of the persecution of the Huguenots (e.g., the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre), this aspect of Desaguliers’ life may have influenced the insistence upon tolerance, especially in matters of religion, as espoused by the Premier Grand Lodge.

At this juncture, I ask that you bear in mind that common themes among the early Protestants included the translation of the Bible into the vernacular and the restoration of the mysteries of the early church (i.e., gnosticism), which they accused Rome of having neglected. The translations of the Bible are now readily available but what of the mysteries? Protestant churches and their ceremonials are, if anything, even more austere than those of the Catholics. For the mysteries, I suggest we need to look to rosicrucianism, as being a more or less separate arm of the Reformation.

Next, we turn to Desaguliers’ protégé, the Rev. Dr. James Anderson (1684-1746), the creator of Freemasonry’s Constitutions. His fame has proved to be more enduring among Freemasons and we may be surprised to find that he was not an orthodox clergyman but rather a member of the Presbyterian, Scottish Reformed Church, having Calvinistic, Covenanter roots. Moreover, ‘...he, as a Presbyterian minister, took over the lease of a chapel in Swallow Street, Piccadilly, from a congregation of French Protestants...’ (i.e., Huguenots; in Clegg, v.1, p.77). Indeed, Desaguliers had been the Pastor there (Cryer, p.158). In this light, the ‘errors, omissions [and] inventions,’ which Waite (p.25) and others have pointed out as characterising his Constitutions, are but the product of Anderson having followed the example of his friend and mentor, Desaguliers, in fabricating modern, Speculative Freemasonry.

Also in this light, we may reflect upon the exasperation expressed by supposedly staunch British Freemasons at the proliferation of degrees in France, after ‘their’ supposedly ‘basic’, ‘pure’ and ‘unadulterated’ Craft crossed the Channel. We can now see that Speculative Freemasonry, although originating in England, had a French influence from its conception and perhaps the French simply recognised the institution for what it was and adroitly interpreted, faithfully developed and further unfolded its allegories and symbols.

Finally, in suggesting the French recognised the institution for what it was, we may naturally ask: ‘What was it?’ The answer which I suggest has to do with the Calvinists’ enthusiasm for translating the Bible into the vernacular and what they found in doing so; with a conflict between their self-righteous ideals and their prejudices; and with their ideas about ‘Primitive Christianity’ and the milieu and legacy of so-called ‘heresies’ in Europe; will have to wait until another night.

THE END

REFERENCES

Carr, Thomas, n.d., ‘The Ritual of the Operative Freemasons’, in Martin’s, British Masonic Miscellany, v.11

Clegg, Robert I., 1946, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, The Masonic History Company, Chicago

Cryer, Neville Barker, 1995, ‘The Geneva Bible and its Contribution to the Development of English Ritual,’ in A Masonic Panorama, Selected Papers of the Reverend Neville Barker Cryer, Australian Masonic Research Council, Melbourne

Cryer, Neville Barker, 1995, ‘Huguenot Freemasons,’ in A Masonic Panorama, Selected Papers of the Reverend Neville Barker Cryer, Australian Masonic Research Council, Melbourne

Hamill, John and Gilbert, Robert, 1992, The First Grand Lodge, (excerpt) www.mastermason.com/3rdnorthern/MasonicHistoryfiles/firstgl.htm

Jones, Bernard E., 1956 (1st 1950) Freemasons’ Guide and Compendium, New and Revised Edition, Harrap, London

Kilner, Margaret K., n.d., The Huguenot Heritage, www.ensignmessage.com/archives/hugher.html

Mackenzie, Kenneth, 1987 (1st 1877), The Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia, Aquarian Press, Wellingborough, Northamptonshire

Mackey, Albert Gallatin, 1917 (org. 1874), Encyclopedia of Freemasonry and its Kindred Sciences Comprising the Whole Range of Arts, Sciences and Literature as Connected with the Institution, McClure Publishing, Philadelphia

Mackey, Albert Gallatin, 1996, The History of Freemasonry, Gramercy Books, Avenel, New Jersey

Maine, George E., 1939, Desaguliers and the March of Militant Masonry, from: web.mit.edu/afs/athena.mit.edu/user/d/r/dryfoo/www/Masonry/Essays/desag.html

Piatigorsky, Alexander, 1999, (1st 1997), Freemasonry: The Study of a Phenomenon, The Harvill Press, London

Times, The, 1961, The Royal Society Tercentenary, The Times Publishing Co., London

Waite, Arthur, n.d., A New Encyclopædia of Freemasonry, (new & revised edition), Rider & Co., London

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Both used building construction, (especially that of temples), as allegories of self-improvement.

[2] These Journeymen Lodges had presumably separated from Guilds, which conducted the five Operative degrees beyond those of the Apprentice and Journeyman or Fellowcraft. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica (1962, v.10, p.966):

In the 14th century the journeymen or yeomen began to set up fraternities in defence of their rights. The formation of these societies marks a cleft within the ranks of some particular class of artisans – a conflict between employers, or master artisans, and workmen. The journeymen combined to protect their special interests, notably as regards hours of work and rates of wages, and they fought with the masters over the labour question in all its aspects. The resulting struggle of organized bodies of masters and journeymen was widespread throughout western Europe, but it was more prominent in Germany than in France or England. This conflict was indeed one of the main features of German industrial life in the 15th century. In England the fraternities of journeymen, after struggling for a while for complete independence, seem to have fallen under the supervision and control of the masters’ gilds; in other words, they became subsidiary or affiliated organs of the older craft fraternities.[3] Conversely, according to Gould ‘...there is not one scrap of evidence that Payne, Desaguliers, and Anderson ... took part in the formation of the Grand Lodge in 1717 ... though all three had a share in the compilation of the First Book of Constitutions’ (Piatigorsky, p.55; q. Gould, 1903, p.286)

[4] Mackenzie also tells us (p.155)

His latter years were clouded by adversity and even by fits of insanity. His great connections had brought him fame but no bread; his unaffected endeavours to aid, instruct, and benefit his fellow-men met with no return; and Desaguliers died in want, obscurity, and, mental darkness, after an ineffectual struggle with the world and its ways.[5] Wren had been a President of the Royal Society (Times, p.29), an institution mentioned below.

[6] The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledgearted in 1662 and originating c.1645.