Post by Tamrin on Oct 17, 2009 19:34:35 GMT 10

From my 2007 paper at the International Conference on the History of Freemasonry (ICHF), in Edinburgh:

IN THE BUILDING TRADES AND AS STONEMASONS

General:

Claudia Opitz, in writing about the Middle Ages, tells us that,1 ‘... women worked in fields that today are more likely to be considered “typically male,” such as metalworking and the construction trade.’ E. Dixon, in an article entitled, ‘Craftswomen in the Livre des Métiers’ (Book of the Crafts),2 set forth a study, focusing on the role of women in thirteenth century Parisian Crafts, as derived from a compilation of, ‘…careful and accurate digests of their traditions, ancient rights and privileges, interior trade-organization, and the like…’ In Dixon’s introductory paragraphs,3 we read that, with only a few specified exceptions, the employment conditions of both craftsmen and craftswomen were exactly the same, being applied with ‘entire impartiality.’4 Toulmin Smith’s English Gilds was also compiled from reports of guilds, etc. (in this case from the late fourteenth century). In it, his daughter Lucy reports,5 by way of post-humus introduction to his late nineteenth century publication:

Claudia Opitz, in writing about the Middle Ages, tells us that,1 ‘... women worked in fields that today are more likely to be considered “typically male,” such as metalworking and the construction trade.’ E. Dixon, in an article entitled, ‘Craftswomen in the Livre des Métiers’ (Book of the Crafts),2 set forth a study, focusing on the role of women in thirteenth century Parisian Crafts, as derived from a compilation of, ‘…careful and accurate digests of their traditions, ancient rights and privileges, interior trade-organization, and the like…’ In Dixon’s introductory paragraphs,3 we read that, with only a few specified exceptions, the employment conditions of both craftsmen and craftswomen were exactly the same, being applied with ‘entire impartiality.’4 Toulmin Smith’s English Gilds was also compiled from reports of guilds, etc. (in this case from the late fourteenth century). In it, his daughter Lucy reports,5 by way of post-humus introduction to his late nineteenth century publication:

Scarcely five out of the [over] five hundred were not formed equally of men and women, which, in these times of the discovery of the neglect of ages heaped upon women, is a noteworthy fact. Even where the affairs were managed by a company of priests, women were admitted as lay members; and they had many of the same duties and claims upon the Gild as the men.6

1Claudia Opitz, 1992, ‘Life in the Late Middle Ages’, in C. Klapische-Zuber (Editor), A History of Women in the West: Vol. II, Silences of the Middle Ages, Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, p.301.

2E. Dixon, ‘Craftswomen in the Livre des Métiers,’ The Economic Journal, Vol. 5, No. 18, 209-228. Jun., 1895.

3Ibid., p.209.

4In Dixon’s closing paragraphs (ibid., p.227), we read:

…there is no trace in the Livre des Métiers of the modern [late 19th century] view that good industrial training and anything above a bare subsistence wage are unnecessary and superfluous for working women, because their labour is merely a bye-product before marriage.5 Toulmin Smith (Editor), 1963 (org. 1870), English Gilds: The Original Ordinances of More than One Hundred Early English Gilds Together with Ye olde Usages of ye Cite of Wynchestre The Ordinances of Worcester The Office of the Mayor of Bristol and The Costomary of the Manor of Tettenhal=Regis from Manuscripts of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, with intro. & glossary, etc. by L.T. Smith and an essay by L. Brentano

6The guilds of priests (e.g., Brentano, in T. Smith, ibid., p.lxxxviii) and those of scholars would more than account for the scarce five that did not admit women. This ratio of more than 99% of guilds admitting women is corroborated by R.F. Gould, (Gould, Robert Freke, 1882, The History of Freemasonry: Its Antiquities, Symbols, Constitutions, Customs, Etc. – Embracing an Investigation of the Records of the Organisations of the Fraternity in England, Scotland, Ireland, British Colonies, France, Germany, and the United States - Derived from Official Sources, Thomas C. Jack, London), who, while he maintained that Stonemasons excluded women, never-the-less wrote of the guilds in his History (v.1, p.90), saying: ‘Not one out of a hundred but recruited their ranks from both sexes...’ He continued (ibid.), saying:

And even in guilds under the management of priests, such as the Brotherhood of ‘Corpus Christ’ of York, begun in 1408, lay members were allowed (of some honest craft), without regard to sex, if ‘of good fame and conversation’ the payments and privileges being the same for the ‘brethren and sisteren.’ Women ‘were sworne upon a book in the same manner as the men.[/size][/blockquote][/quote]

Würzburg:

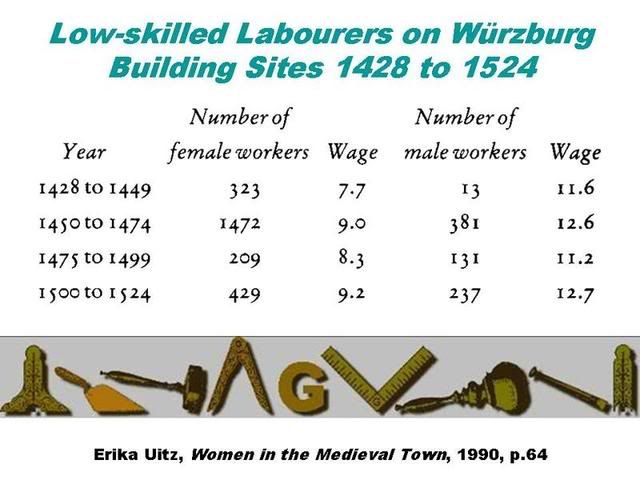

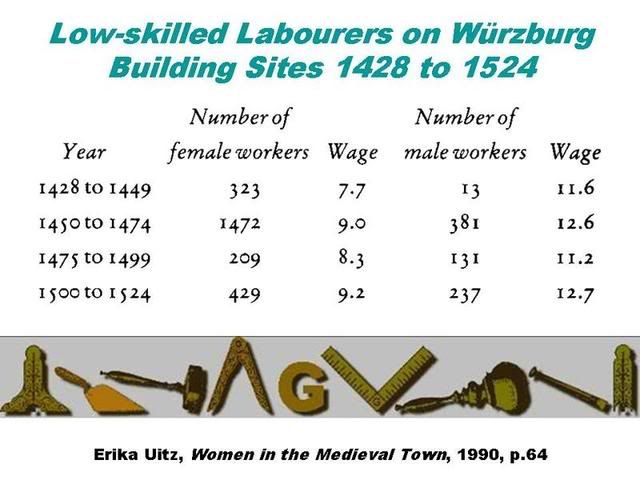

Erika Uitz, in her book, Women in the Medieval Town, while noting the generally lower wages of females workers, remarks:1

According to Uitz,2 these pay conditions were not exceptional in the region and was typically for heavy work, such as the carrying of stones and mortar. This chart of those figures further emphasizes the ratio of women to men working on those building sites being, on average, more than three to one.

Thus, women not only endured the fatigues of labour in the building trades but also, at least in the Würzburg case, vastly outnumbered the men! Indeed, because of the prevalence of women and their acceptance of lower wages and relatively high productivity, the journeymen’s lodges, fearing for their own prospects, agitated for their exclusion, and that of foreigners, from most trades in the late middle ages. Claudia Opitz , described tension over pay rates towards the end of the middle ages, saying:3

Erika Uitz, in her book, Women in the Medieval Town, while noting the generally lower wages of females workers, remarks:1

Even under such pay conditions, female employment rates were high. On Würzburg building sites, for example, a large amount of female labour was employed on a daily basis between 1428 and 1524. The low-skilled labourers received the following average wage, reckoned in pfennigs:

According to Uitz,2 these pay conditions were not exceptional in the region and was typically for heavy work, such as the carrying of stones and mortar. This chart of those figures further emphasizes the ratio of women to men working on those building sites being, on average, more than three to one.

Thus, women not only endured the fatigues of labour in the building trades but also, at least in the Würzburg case, vastly outnumbered the men! Indeed, because of the prevalence of women and their acceptance of lower wages and relatively high productivity, the journeymen’s lodges, fearing for their own prospects, agitated for their exclusion, and that of foreigners, from most trades in the late middle ages. Claudia Opitz , described tension over pay rates towards the end of the middle ages, saying:3

The competition between various interest groups raged all the more fiercely, especially when times were hard. Journeymen played a key role in these battles; since female maids and apprentices earned a third less on average, the men fought successfully to have them excluded from virtually all guilds by the end of the Middle Ages.4

1Erika Uitz, 1990, Women in the Medieval Town, Barrie & Jenkins, London, p.64.

2Ibid.

3Claudia Opitz, op. cit., p.302.

4According to the Encyclopædia Britannica (1962, v.10, p.966):

In the 14th century the journeymen or yeomen began to set up fraternities in defence of their rights. The formation of these societies marks a cleft within the ranks of some particular class of artisans—a conflict between employers, or master artisans, and workmen. The journeymen combined to protect their special interests, notably as regards hours of work and rates of wages, and they fought with the masters over the labour question in all its aspects. The resulting struggle of organized bodies of masters and journeymen was widespread throughout western Europe, but it was more prominent in Germany than in France or England. This conflict was indeed one of the main features of German industrial life in the 15th century. In England the fraternities of journeymen, after struggling for a while for complete independence, seem to have fallen under the supervision and control of the masters’ gilds; in other words, they became subsidiary or affiliated organs of the older craft fraternities.

Strasbourg:

Returning to Erika Uitz’s account, we are also told of:1

While not denying the possibility of the account, Gould argued against its probability, maintaining:6

According to Gould,10 until the capture of the city by France in 1681, the headquarters of the German Stonemasons was in Strasbourg (even as late as 1760 the Strasbourg lodge still claimed tribute from the lodges of Germany). Indeed, Albert Mackey, in his Encyclopedia,11 cites the theory, ‘which places the organization of the Order of Freemasonry at the building of the Cathedral of Strasburg, in the year 1275.’ If so, Sabina von Steinbach would have been one of Freemasonry’s founders.

Returning to Erika Uitz’s account, we are also told of:1

… the building and building-related trades in the late Middle Ages: Written and pictorial sources suggest that women were employed in the hard physical work involved in the building, mortar-mixing, roof-making, and glazier trades…More specifically, she goes on to say:2 ‘In Strasbourg from 1452 to 1453, two women joined the masons’ guild and were simultaneously granted the right to town citizenship’. Also in Strasbourg, Gould refers to an account,3 which he says was elsewhere reported as being of ‘undoubted authenticity’,4 but which, nonetheless, he doubts, solely on the basis of the involvement of a woman), whereby the porch of its thirteenth century cathedral was completed by Sabina, a skilful mason and the daughter of the cathedral’s famous architect, Erwin of Steinbach. Sabina and her father are depicted at the Cathedral. According to the description accompanying these pictures, Erwin is holding the plans of the cathedral and Sabina is holding a hammer and the Book of Constitutions of the Mason’s Gild.5

While not denying the possibility of the account, Gould argued against its probability, maintaining:6

Apprenticeship and travel were essentials, and these ordeals, though the fortitude of a determined woman might have sustained her throughout the labours of the former, it is scarcely to be conceived that a member of the gentler sex could have endured the perils and privations of the latter.Gould’s baseless and peculiar, class laden Victorian condescension would, if true, have prevented wives and daughters from accompanying their husbands and fathers and would have precluded women from pilgrimages, migrations and tramping in search of domestic work.7 We know that women were employed as carpenters8 and in other trades that also required travel.9

According to Gould,10 until the capture of the city by France in 1681, the headquarters of the German Stonemasons was in Strasbourg (even as late as 1760 the Strasbourg lodge still claimed tribute from the lodges of Germany). Indeed, Albert Mackey, in his Encyclopedia,11 cites the theory, ‘which places the organization of the Order of Freemasonry at the building of the Cathedral of Strasburg, in the year 1275.’ If so, Sabina von Steinbach would have been one of Freemasonry’s founders.

1Erika Uitz, op. cit., p.61.

2Ibid.

3R.F. Gould, op. cit., v.i, pp.175/6.

4G.F. Fort, op.cit., p.81.

5Private Email to author, 1 October 2006.

6R.F. Gould, op.cit., v.i, p. 176.

7We also know that some women have even distinguished themselves as explorers <http://www.distinguishedwomen.com/subject/explore.html>.

8R.F. Gould, op. cit., v.i, p.176. & Crowe, op. cit.

9Journeywomen page <http://www.geocities.com/womenmasons/journey.html>

10R.F. Gould, op. cit., v.1, p.173.

11Albert Gallatin, Mackey, 1917 (org. 1874), Encyclopedia of Freemasonry and its Kindred Sciences Comprising the Whole Range of Arts, Sciences and Literature as Connected with the Institution, McClure Publishing, Philadelphia, p.704.