|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 30, 2008 9:03:47 GMT 10

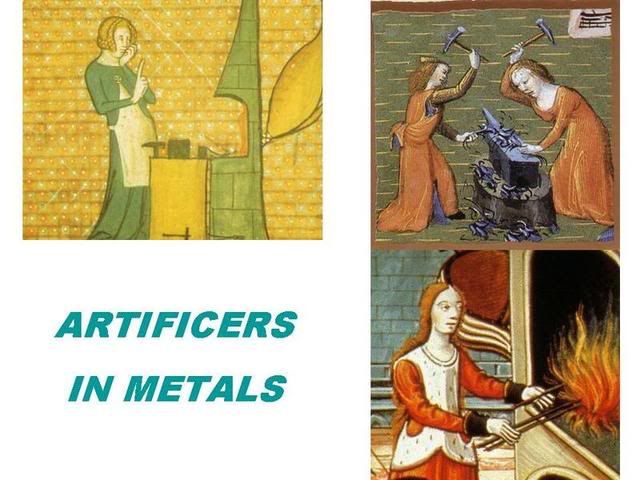

CRAFTSWOMEN

in the Old Charges, in Building Trades and as Stonemasons Philip Carter, International Conference on the History of Freemasonry, Edinburgh, 27 May 2007 To avoid distraction, to comment on this thread please do so on the appropriate thread, under Topics.1ABSTRACT: The author shows contemporary illustrations depicting women in these trades, provides references to ‘sisters’, ‘dames,’ and to ‘she who is to be made a Mason,’ examines reports of women involved in the building trades (even an instance of them vastly outnumbering the men), compares this evidence with that contained in the 14th Century returns of English Gilds, and explores the implications of Stonemasons forming trade combinations with other artisans. He then proceeds to consider the privileged position of the wives and daughters of tradesmen and the special status of their widows. Finally, he acknowledges specific female Stonemasons, ranging from Sabina von Steinbach of 13th Century Strasburg, to Mary Banister of 18th Century London. 2S.C.R.L. (Southern California Research Lodge), 1989, ‘Interview with H.R.H. The Duke of Kent, Grand Master’, (transcript of interview broadcast on 9 July 1986), in The NSW Freemason, v.21, no.6, United Grand Lodge of NSW, Sydney, p.13. 3See Appendix. 4W.R. Day, in S. Scott-Young, 1918, ‘Women and Freemasonry’, in Transactions of the Sydney Lodge of Research, No. 290, U.G.L., N.S.W., Vol. V., Bloxham & Chambers, Sydney, p.42. See also George Smith, 1783, The Use and Abuse of Freemasonry: A Work of the Greatest Utility to the Brethren of the Society, to Mankind in General and to the Ladies in Particular, printed by the author, sold by G. Kearsley, London. 5Bob James, 1992, ‘Where are all the Women in Labour History?,’ in Whitlam, Gough, et al., A Century of Social Change, Pluto Press, Leichhardt, NSW. 6Kelvin H. Perdriau, April, 2001, ‘ Innovation: A Long-standing Masonic Attribute’, in The NSW Freemason, v.33, n.2, UGL of NSW & ACT, Sydney. 7Brian W. Gastle, Spring 2003, ‘ Breaking the Stained Glass Ceiling: Mercantile Authority, Margaret Paston, and Margery Kempe’, Studies in the Literary Imagination. |

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 30, 2008 10:59:55 GMT 10

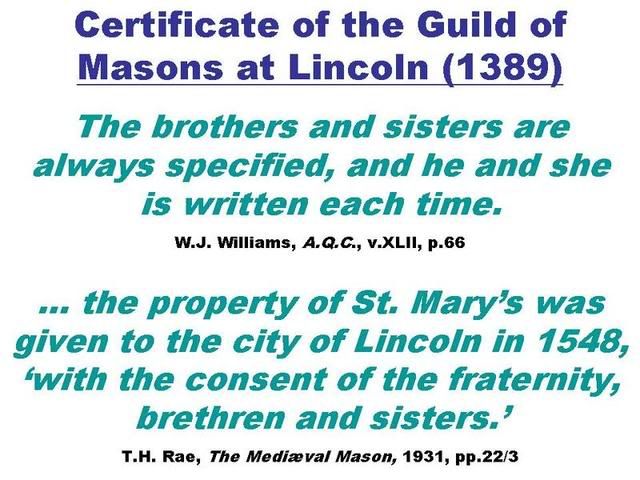

1W.J. Williams, ‘ Gild of Masons at Lincoln’, in Ars Quatuor Coronatorum ( A.Q.C.), Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge No. 2076, London, v. XLII, 1931, pp.64/67. 2A.Q.C., v. LIV, pp.108/110; v. XLIII, p.200; v. XLV, p.293; v. LIV, p.108/110; & v. LVI, p.293. 3Knoop and Jones, A.Q.C., v. XLV, p.293. However, prior to the sixteenth century, with the Reformation’s ‘ disendowment of the religion of the misteries’ ( Encylopædia Britannica, 1962, v.10, p.966), all guilds were predominantly social or religious in character, with some also having a trade as a qualification of membership (Ernest Pooley, 1945, The Guilds of the City of London, William Collins, London, p.8). 4E.G., Bernard Jones, 1956, Freemason’s Guide and Compendium (new & revised edition), A. Lewis, London, p.70. 5Toulmin Smith (Editor), 1963 (org. 1870), English Gilds: The Original Ordinances of More than One Hundred Early English Gilds Together with Ye olde Usages of ye Cite of Wynchestre The Ordinances of Worcester The Office of the Mayor of Bristol and The Costomary of the Manor of Tettenhal=Regis from Manuscripts of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, with intro. & glossary, etc. by L.T. Smith and an essay by L. Brentano[/i], Oxford University Press, London (for The Early English Text Society), pp.xxi: And Gastle, op. cit. 6George M. Martin (compiler), n.d., British Masonic Miscellany, David Winter & Son, Dundee, v.1, pp.6, 13 & 19. 7‘ ... In case anyone should think that such a title meant perhaps only the Master’s living partner’, Rev. N.B. Cryer tells us (1995, A Masonic Panorama: Selected Papers of the Reverend Neville Barker Cryer, Australian Masonic Research Council, Williamstown, Vic. p.23): …it is worth noting that as late as 1683 the records of the Lodge of Mary’s Chapel in Edinburgh provide an instance of a female occupying the position of ‘Dame’ or ‘Mistress’ in a masonic sense. She was a widow of a mason but she exercised an equal right with other operative masons and took the same ceremonies. 8York Manuscript No. 4, 1693. 9Dudley Wright, 1922, Woman and Freemasonry, William Rider & Son, London, p.95. 10Masonic Times, May 1995, Rochester, N.Y. 11To those who claim ‘she’ is a mistranslation, we may ask them to consider that, if translated and transcribed from an earlier document, the work was likely to have been done by an esteemed master, well acquainted with the genuine imperatives of the Craft. Further, the manuscript seems to have been handed on to, read and accepted by subsequent masters without them perceiving any need for amendment or correction. As A.F.A. Woodford acknowledged (Editor, 1878, Kenning’s Masonic Cycopædia and Handbook of Masonic Archæology, History and Biography, George Kenning, London, p.146): The words, ‘hee or shee,’ in York MS. No. 4, are only equivalent to what may be shown in other Guild regulations, and the suggestion that ‘shee’ should read ‘they,’ though made by so great an authority as Bro. D. Murray Lyon, is not, we venture to think, tenable in the face of the evidence of female Guild membership of some kind which may be adduced. The usage, as far as the Masons are concerned, proves the great antiquity of the instruction.

|

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 30, 2008 19:46:22 GMT 10

IN THE BUILDING TRADES AND AS STONEMASONS 1Claudia Opitz, 1992, ‘Life in the Late Middle Ages’, in C. Klapische-Zuber (Editor), A History of Women in the West: Vol. II, Silences of the Middle Ages, Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, p.301. 2E. Dixon, ‘Craftswomen in the Livre des Métiers,’ The Economic Journal, Vol. 5, No. 18, 209-228. Jun., 1895. 3Ibid., p.209. 4In Dixon’s closing paragraphs ( ibid., p.227), we read: …there is no trace in the Livre des Métiers of the modern [late 19th century] view that good industrial training and anything above a bare subsistence wage are unnecessary and superfluous for working women, because their labour is merely a bye-product before marriage. 5T. Smith, op. cit., p.xxx. 6The guilds of priests (e.g., Brentano, in T. Smith, ibid., p.lxxxviii) and those of scholars would more than account for the scarce five that did not admit women. This ratio of more than 99% of guilds admitting women is corroborated by R.F. Gould, (Gould, Robert Freke, 1882, The History of Freemasonry: Its Antiquities, Symbols, Constitutions, Customs, Etc. – Embracing an Investigation of the Records of the Organisations of the Fraternity in England, Scotland, Ireland, British Colonies, France, Germany, and the United States - Derived from Official Sources, Thomas C. Jack, London), who, while he maintained that Stonemasons excluded women, never-the-less wrote of the guilds in his History (v.1, p.90), saying: ‘ Not one out of a hundred but recruited their ranks from both sexes...’ He continued ( ibid.), saying: And even in guilds under the management of priests, such as the Brotherhood of ‘Corpus Christ’ of York, begun in 1408, lay members were allowed (of some honest craft), without regard to sex, if ‘of good fame and conversation’ the payments and privileges being the same for the ‘brethren and sisteren.’ Women ‘were sworne upon a book in the same manner as the men. |

|

|

|

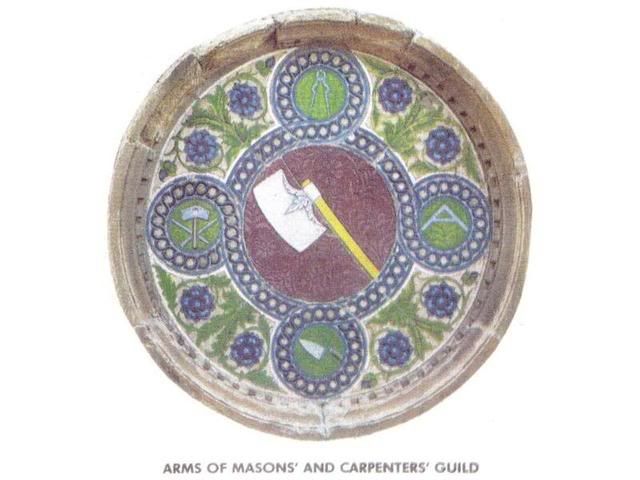

Post by Tamrin on Aug 30, 2008 20:04:24 GMT 10

1H.L. Haywood, 1951, Freemasonry and the Bible, William Collins, Sons & Co. Ltd, Great Britain, p.9. See also George F. Fort, 1884, The Early History and Antiquities of Freemasonry, As Connected with Ancient Norse gilds, and the Oriental and Mediæval Building Fraternities, Bradley & Co., Philadelphia, p.434. 2T. Smith, op.cit. & R.F. Gould, v.1, p.90: See also Women in the Medieval Guilds by Lady Magdelene Saunders <www.lothene.org/feudalist/guilds.html>. 3Thomas Carr, n.d., ‘Operative Free Masons and Operative Free Masonry’, in George M. Martin (compiler), op. cit., v.6, p.116. 4E.G., Fred J.W. Crowe, 1914, ‘The Free Carpenters’, in Rylands & Songhurst (Editors), AQC Vol. XXVII, Quatuor Coronati Lodge No. 2076 (E.C.), London, pp.5/19. 5R.F. Gould, op. cit., v.1, p.94 6Nevertheless, Gould maintained ( ibid.) stonemasonry was a special case, in so far as, according to his unfounded assumption, women were excluded from the craft. Also note, there had been something of a dispute between the two trades as to precedence (René Guénon, 2004 org. 1964, Studies in Freemasonry & the Compagnonnage, translated by Fohe, Bethell & Allen, Sophia Perennis, Hillsdale, NY, pp.39/42).

|

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 30, 2008 22:32:53 GMT 10

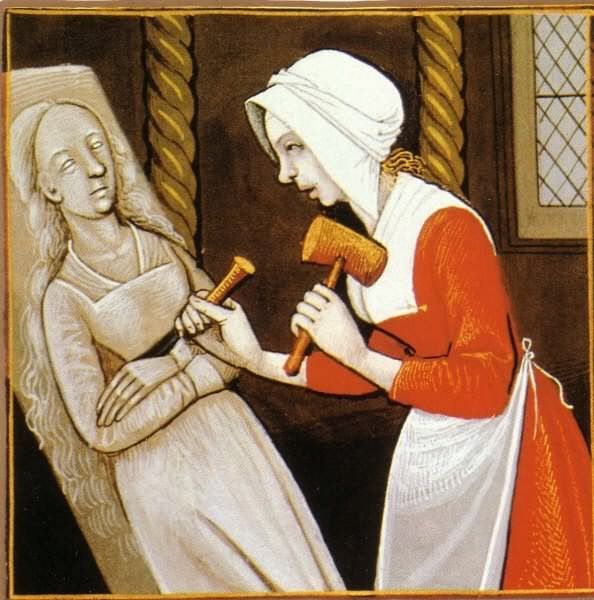

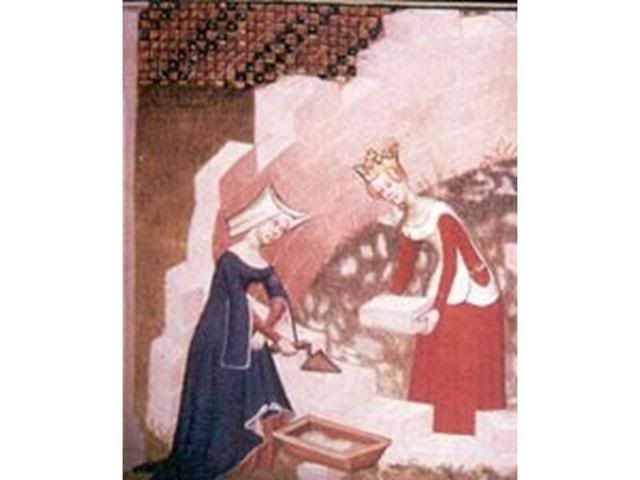

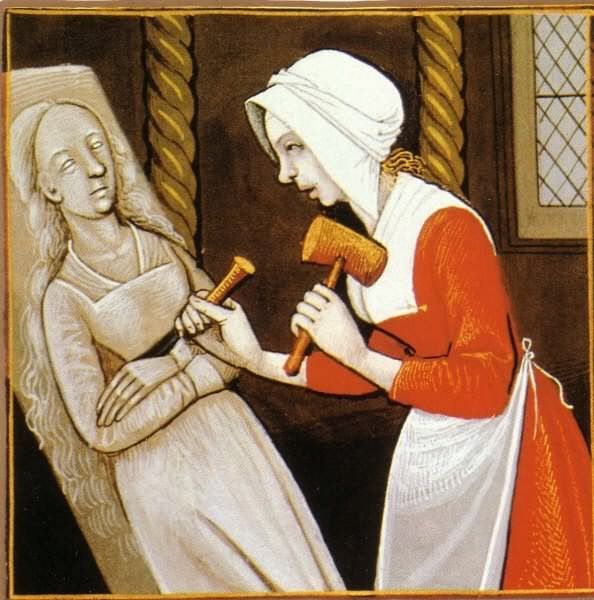

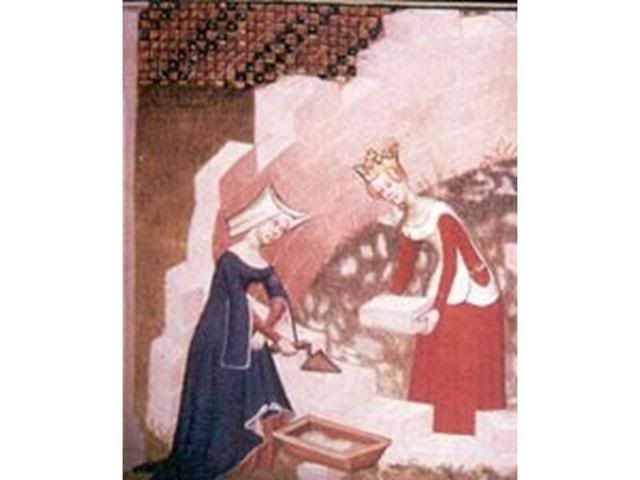

‘Sculptor,’ Giovanni Boccaccio, Le Livre des Cleres et Nobles Femmes, MS Fr. 598, fol. 100v; French, fifteenth century, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. Paul Naudon, (trans. J.Graham), 2005, The Secret History of Freemasonry: Its Origins and Connection to the Knights Templar, Inner Traditions, Rochester, Vermont, p.150. 2T. Smith, op. cit., pp.cxxxi/cxxxii. 3While at this time and place, Gild-brothers were prohibited from employing women other than their wives and daughters (T. Smith, ibid., footnote, p.cxxxii). There remains the question of whether or not daughters (orphaned or not), like their widowed mothers, had, by virtue of their gild membership, the subsequent right to confer upon their husbands the freedom of the guild, provided their husbands were already in the trade. Brentanto implies this by reference to ‘special favours’ in such cases (p.cli). 4MacBride’s doubt (A.S. Macbride, 1924, Speculative Masonry, Southern Publishers, Kingsport, Tennessee, p.207) presents something of a paradox since, if justified, new doubts arise as to what the involvement and admission of widows entailed as, if not permitted to do the physical work of a stonemason and if not admitted to the mysteries and privileges of the craft, one may wonder in what sense they were members. 5Ibid. |

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 30, 2008 22:54:42 GMT 10

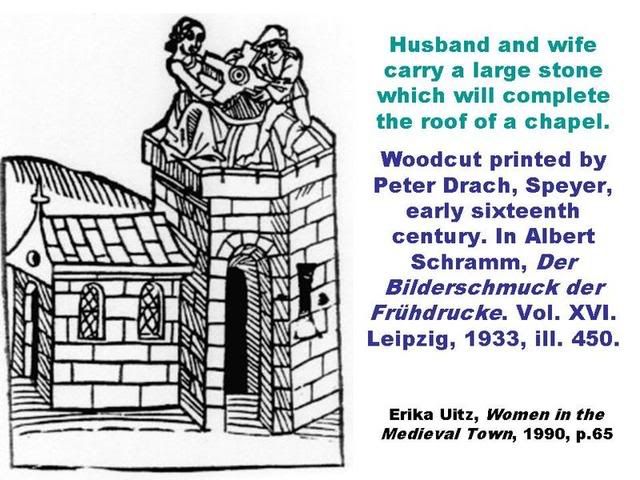

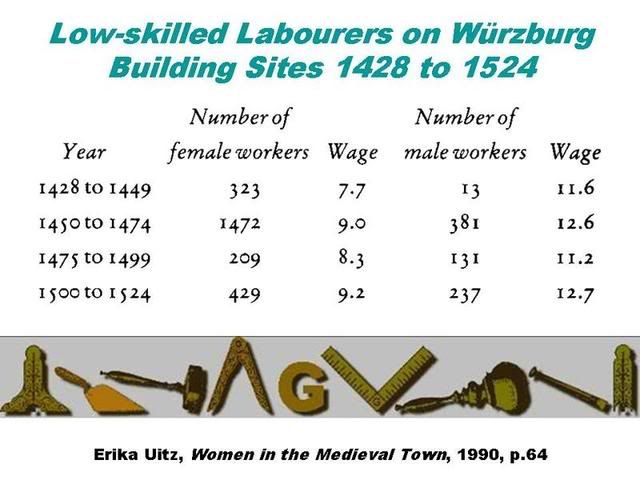

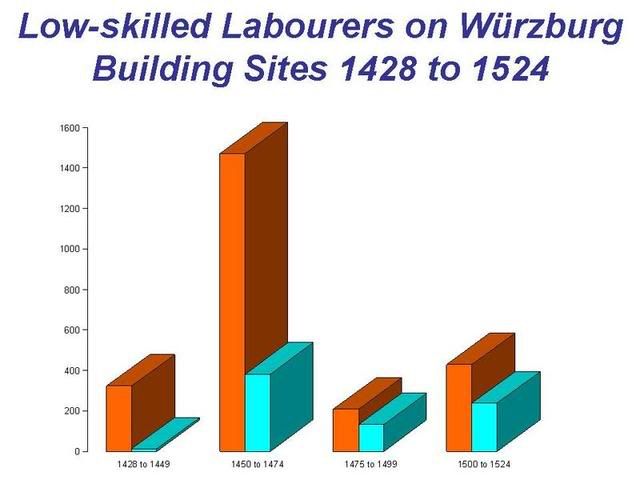

1Erika Uitz, 1990, Women in the Medieval Town, Barrie & Jenkins, London, p.64. 2Ibid.3Claudia Opitz, op. cit., p.302. 4According to the Encyclopædia Britannica (1962, v.10, p.966): In the 14th century the journeymen or yeomen began to set up fraternities in defence of their rights. The formation of these societies marks a cleft within the ranks of some particular class of artisans—a conflict between employers, or master artisans, and workmen. The journeymen combined to protect their special interests, notably as regards hours of work and rates of wages, and they fought with the masters over the labour question in all its aspects. The resulting struggle of organized bodies of masters and journeymen was widespread throughout western Europe, but it was more prominent in Germany than in France or England. This conflict was indeed one of the main features of German industrial life in the 15th century. In England the fraternities of journeymen, after struggling for a while for complete independence, seem to have fallen under the supervision and control of the masters’ gilds; in other words, they became subsidiary or affiliated organs of the older craft fraternities.

|

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 30, 2008 23:22:48 GMT 10

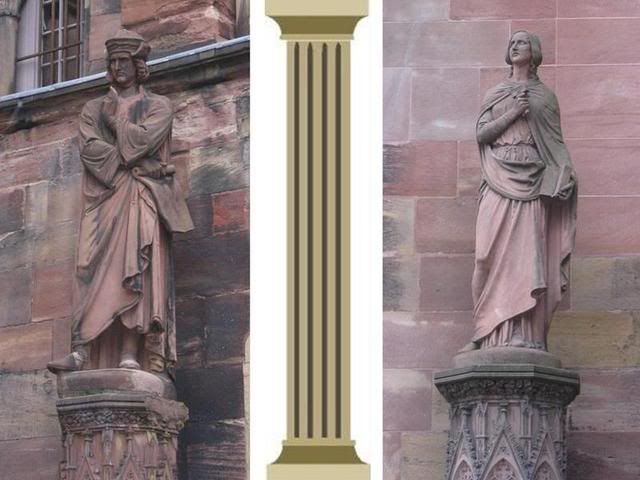

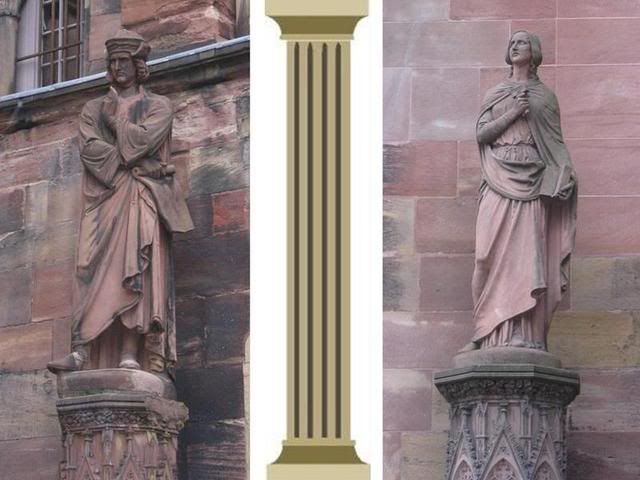

Statues of Erwin & Sabina von Steinbach: Strasbourg’s Notre Dame Cathedral. Statues of Erwin & Sabina von Steinbach: Strasbourg’s Notre Dame Cathedral.Erika Uitz, op. cit., p.61. 2Ibid.3R.F. Gould, op. cit., v.i, pp.175/6. 4G.F. Fort, op.cit., p.81. 5Private Email to author, 1 October 2006. 6R.F. Gould, op.cit., v.i, p. 176. 7We also know that some women have even distinguished themselves as explorers <http://www.distinguishedwomen.com/subject/explore.html>. 8R.F. Gould, op. cit., v.i, p.176. & Crowe, op. cit.9Journeywomen page <http://www.geocities.com/womenmasons/journey.html> 10R.F. Gould, op. cit., v.1, p.173. 11Albert Gallatin, Mackey, 1917 (org. 1874), Encyclopedia of Freemasonry and its Kindred Sciences Comprising the Whole Range of Arts, Sciences and Literature as Connected with the Institution, McClure Publishing, Philadelphia, p.704. |

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 31, 2008 8:42:37 GMT 10

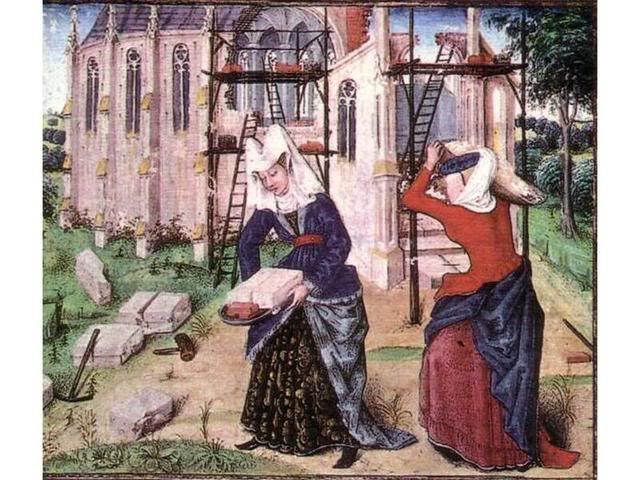

Masons constructing the city wall (detail) Collected Works of Christine de Pisan: Citédes Dames. MS. Harley 4431, f. 290. French Fifteenth century. British Library, London. Christine de Pisan (with trowel): a medieval speculative Freemason, allegorically depicted building an ideal city for worthy women with the assistance of ‘Reason’ (with crown). E. McLeod, 1976, The Order of the Rose: The Life and Ideas of Christine de Pizan, Chatto & Windus, London. Paul Naudon (op. cit., p.126), writing of Trinity Hospital, tells us of women instructors: At the time of the hospital’s reorganization, supported by an act of Parliament on July 1, 1547, it was decided that children of the poor would also be raised there and educated in craft techniques by male and female workers in return for the privilege of obtaining, in six years’ time recognition as masters in their crafts without the requirement of any fee or masterpiece… Two acts of Parliament, one of December 3, 1672, and one of August 22, 1798, specifically confirmed ‘the rule over the rights and privileges of those who taught the art of craft and masonry in the hospital of the Trinity and those who have learned it in said hospital. 2Robert Ingham Clegg, 1921 (org. 1898), Mackey’s History of Freemasonry, (new, revised & enlarged edition), The Masonic History Company, Chicago, v.3, p.690. 3In his Encyclopedia (op. cit., p.841), Mackey says: Squaremen. The companies of wrights, slaters, etc., in Scotland were called ‘Squaremen.’ They had ceremonies of initiation, and a word, sign, and grip, like the Masons. Lyon (Hist. Of the L. at Edinb., p.23) says: ‘The “Squaremen Word” was given in conclaves of journeymen and apprentice wrights, slaters, etc., in a ceremony in which the aspirant was blindfolded and otherwise “prepared;” he was sworn to secrecy, had word, grip and sign communicated to him, and was after¬wards invested with a leather apron. The entrance to the apartment, usually a public house, in which the “brithering” was performed was guarded, and all who passed had to give the grip. The fees were spent in the entertainment of the brethren present. Like the Masons, the Squaremen admitted non-operatives.’ In the St. Clair Charter of 1628, among the representatives of the Masonic Lodges, we find the signature of ‘George Lidde’’, deakin of squarmen and now quartermaister.’ This would show that there must have been an intimate connection between the two societies or crafts. 4By failing to connect this decision with the wider movement at the time, which sought to exclude women from many trades, Clegg (op. cit.) leaves the reader with the impression that Stonemasonry was, and always had been, a special case. Here Clegg, interpolates his own subjective opinion, stating (ibid.): But this custom, growing into an evil, in time the females acting independently and assuming the position and exercising the prerogatives of Master Masons, the Lodge of Edinburgh found it necessary at length to correct the abuse and to restrict the privilege by compelling the females to undertake the work and employ the journeymen under the direction of a Master Mason, who, acting for the widow, discharged the duties without receiving compensation (which was strictly forbidden) and gave her the profits. |

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 31, 2008 9:00:26 GMT 10

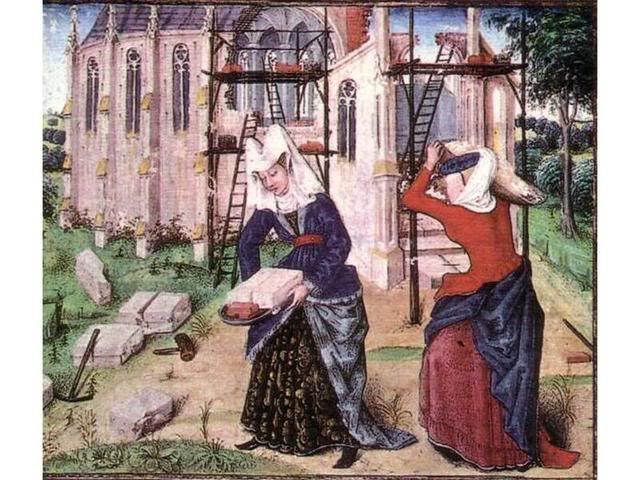

Women Builders Women Builders (detail). Roman des Girart von Roussillon, Cod. 2549, f.167v, Flemish, 1447, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. T. Herdman Rae, 1931, The Mediæval Mason: A Sketch of the Times and the Men, Manchester Association for Masonic Research (reprinted from their transactions), pp.22/3. 2Reasoning from the mistaken 'No Women!' article of faith, Rae then maintains (ibid.) that the mention of 'sisters' casts doubt on whether or not the guild still retained its 'operative' nature. However, on the one hand, the wording of the Certificate, including both brothers and sisters and referring to the 'operative' practice of taking apprentices, should, if connected with this particular lodge, put his doubt to rest. On the other hand, were his doubt well founded, then this example would be even more relevant to the 'speculative' nature of modern, mainstream Freemasonry. |

|

|

|

Post by Tamrin on Aug 31, 2008 9:22:05 GMT 10

1Cyril Northwood Batham, ‘The London Company of Masons,’ in Tony Pope (Editor), Freemasonry in England and France: Collected Papers of C.N. Batham, Australian Masonic Research Council, Williamstown, Vic., Australia, p.102. 2Marjorie Keniston McIntosh, 2005, Working Women in English Society, 1300-1620, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p.236. 3B. Jones, op. cit., pp.77/8. 4The Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons’ website <www.hfaf.org/womenmsns.htm>.

|

|