Post by Tamrin on Mar 29, 2014 6:23:14 GMT 10

The fallacy of genetic determinism is to suppose that the genes "make' the organism. It is a

basic principle of developmental biology that organisms undergo a continuous development

from conception to death, a development that is the unique consequence of the interaction

of the genes in their cells, the temporal sequence of environments through which the organisms

pass, and random cellular processes that determine the life, death, and transformation of cells

The great attraction of cultural anthropology in the past was precisely that it seemed to offer such

a richness of independent natural experiments; but unfortunately it is now clear that there has

been a great deal of historical continuity and exchange among those "independent" experiments,

most of which have felt the strong effect of contact with societies organized as modern states

There are some things in the world that we will never know and many that we will never know exactly.

Each domain of phenomena has its characteristic grain of knowability. Biology is not physics, because

organisms are such complex physical objects, and sociology is not biology because human societies

are made by self-conscious organisms. By pretending to a kind of knowledge that it cannot achieve,

social science can only engender the scorn of natural scientists and the cynicism of the humanists

It is characteristic of the design of scientific research that exquisite attention is devoted to methodo-

logical problems that can be solved, while the pretense is made that the ones that cannot be solved

are really nothing to worry about. On the one hand, biologists will apply the most critical and de-

manding canons of evidence in the design of measuring instruments or in the procedure for taking

an unbiased samples of organisms to be tested, but when asked whether the conditions in the labor-

atory are likely to be relevant to the situation in nature, they will provide a hand-waving intuitive argu-

ment filled with unsubstantiated guesses and prejudices because, in the end, that is all they can do

The division between those who try to learn about the world by manipulating it and those who can

only observe it had led, in natural science, to a struggle for legitimacy. The experimentalists look

down on the observers as merely telling uncheckable just-so stories, while the observers scorn the

experimentalists for their cheap victories over excessively simple phenomena. In biology the two

camps are now generally segregated in separate academic departments where they can go about

their business unhassled by their unbelievers. But the battle is unequal because the observers'

consciousness of what it is to do "real" science has been formed in a world dominated by the man-

ipulators of nature. The observers then pretend to an exactness that they cannot achieve and they

attempt to objectify a part of nature that is completely accessible only with the air of subjective tools

An important consequence of the unique interaction between internal and external forces ...

is that knowledge of genetic differences contain no information at all about whether a

characteristic can be changed by environmental and social arrangements. The most elementary

error about genetics and development is to suppose that "genetic" is the opposite of "change-

able" and that an answer to the question "how much can a trait be changed by social, historical

and individual circumstances" is given by an answer to the question "how important are genes?"

To say that genetic differences are relevant to hetero- and homosexuality is not, however,

to say that there are "genes for homosexuality" or even that there is a "genetic tendency to

homosexuality." This critical point can be illustrated by an example I owe to the philosopher

of science, Elliott Sober. If we look at the chromosomes of people who knit and those who

do not, we will find that with few exceptions, knitters have two X chromosomes [women],

while people with one X and one Y chromosome [men] almost never knit. Yet it would be

absurd to say that we had discovered genes for knitting. ... n our culture, women are taught

to knit and men are not. The beauty of this example is its historical (and geographical) contin-

gency. Had we made our observations before the end of the eighteenth century (or even now

in a few Irish, Scottish and Newfoundland communities), the results would have been reversed.

Hand knitting was men's works before the introduction of knitting machines around 1790, and was

turned into a female domestic occupation only when mechanization made it economically marginal

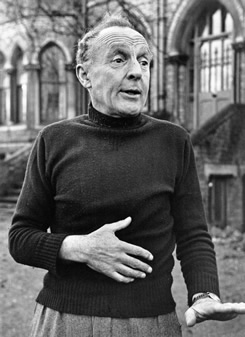

Richard C. Lewontin

American evolutionary biologist and geneticist (Not in Our Genes)

(Born this day 1929)

Science fiction stories are the Gedanken experiments of social science

basic principle of developmental biology that organisms undergo a continuous development

from conception to death, a development that is the unique consequence of the interaction

of the genes in their cells, the temporal sequence of environments through which the organisms

pass, and random cellular processes that determine the life, death, and transformation of cells

The great attraction of cultural anthropology in the past was precisely that it seemed to offer such

a richness of independent natural experiments; but unfortunately it is now clear that there has

been a great deal of historical continuity and exchange among those "independent" experiments,

most of which have felt the strong effect of contact with societies organized as modern states

There are some things in the world that we will never know and many that we will never know exactly.

Each domain of phenomena has its characteristic grain of knowability. Biology is not physics, because

organisms are such complex physical objects, and sociology is not biology because human societies

are made by self-conscious organisms. By pretending to a kind of knowledge that it cannot achieve,

social science can only engender the scorn of natural scientists and the cynicism of the humanists

It is characteristic of the design of scientific research that exquisite attention is devoted to methodo-

logical problems that can be solved, while the pretense is made that the ones that cannot be solved

are really nothing to worry about. On the one hand, biologists will apply the most critical and de-

manding canons of evidence in the design of measuring instruments or in the procedure for taking

an unbiased samples of organisms to be tested, but when asked whether the conditions in the labor-

atory are likely to be relevant to the situation in nature, they will provide a hand-waving intuitive argu-

ment filled with unsubstantiated guesses and prejudices because, in the end, that is all they can do

The division between those who try to learn about the world by manipulating it and those who can

only observe it had led, in natural science, to a struggle for legitimacy. The experimentalists look

down on the observers as merely telling uncheckable just-so stories, while the observers scorn the

experimentalists for their cheap victories over excessively simple phenomena. In biology the two

camps are now generally segregated in separate academic departments where they can go about

their business unhassled by their unbelievers. But the battle is unequal because the observers'

consciousness of what it is to do "real" science has been formed in a world dominated by the man-

ipulators of nature. The observers then pretend to an exactness that they cannot achieve and they

attempt to objectify a part of nature that is completely accessible only with the air of subjective tools

An important consequence of the unique interaction between internal and external forces ...

is that knowledge of genetic differences contain no information at all about whether a

characteristic can be changed by environmental and social arrangements. The most elementary

error about genetics and development is to suppose that "genetic" is the opposite of "change-

able" and that an answer to the question "how much can a trait be changed by social, historical

and individual circumstances" is given by an answer to the question "how important are genes?"

To say that genetic differences are relevant to hetero- and homosexuality is not, however,

to say that there are "genes for homosexuality" or even that there is a "genetic tendency to

homosexuality." This critical point can be illustrated by an example I owe to the philosopher

of science, Elliott Sober. If we look at the chromosomes of people who knit and those who

do not, we will find that with few exceptions, knitters have two X chromosomes [women],

while people with one X and one Y chromosome [men] almost never knit. Yet it would be

absurd to say that we had discovered genes for knitting. ... n our culture, women are taught

to knit and men are not. The beauty of this example is its historical (and geographical) contin-

gency. Had we made our observations before the end of the eighteenth century (or even now

in a few Irish, Scottish and Newfoundland communities), the results would have been reversed.

Hand knitting was men's works before the introduction of knitting machines around 1790, and was

turned into a female domestic occupation only when mechanization made it economically marginal

Richard C. Lewontin

American evolutionary biologist and geneticist (Not in Our Genes)

(Born this day 1929)

Science fiction stories are the Gedanken experiments of social science